|

Centaurea calcitrapa

|

|

|

|

Scientific name

|

Centaurea calcitrapa

|

|

Additional name information:

|

L.

|

|

Common name

|

purple starthistle, red star thistle, red starthistle, St. BarnabyÛªs thistle, golden starthistle

|

|

Synonymous scientific names

|

none known

|

|

Closely related California natives

|

0

|

|

Closely related California non-natives:

|

11

|

|

Listed

|

CalEPPC List B,CDFA B

|

|

By:

|

John M. Randall

|

|

Distribution

|

|

|

HOW DO I RECOGNIZE IT?

Distinctive features:

|

Purple

starthistle (Centaurea calcitrapa) is an annual to perennial thistle with

a mounding growth habit and heads of purple flowers surrounded by long, stout,

sharp-pointed spines. Plants form rosettes in their first growing season, the

leaves deeply pinnately lobed and gray-hairy with light-colored midribs; older

rosettes have a circle of spines in the center. Mature plants are one to four

feet high, densely and rigidly branched, and have numerous flowerheads (Roche

and Roche 1990). Purple starthistle is similar to Iberian starthistle

(Centaurea iberica), which is also found in California,

but which differs in having seeds that are topped by a crown of bristles. The

young heads of purple starthistle are reportedly edible like an artichoke

(Allred and Lee 1996).

|

|

Description:

|

Asteraceae. Usually behaves as a biennial, but may be an annual or a short-lived perennial under some conditions. Plants form rosettes in their first growing season. Leaves of young rosettes more or less gray-tomentose with light-colored midribs; leaves of older plants glabrous and resin-dotted. Older rosettes often develop a ring of stout spines at the center before bolting. Plants usually bolt during second growing season. |

|

Mature plants 0.5 to 4 ft (20-130 cm) tall, often more or less mounded and densely and rigidly branched. Lower leaves on bolted plants are 4-8 in (10-20 cm) long and more or less deeply lobed. Flower heads many, each surrounded by leaves, involucres 0.25-0.3 in (6-8 mm) in diameter, 0.6-0.8 in (1.5-2 cm) long, ovoid in outline, main phyllaries greenish or straw-colored and tipped with a stout spine 0.4-1 in (1-2.5 cm) long, spine with a fringe of small spines at base. There are 25-40 flowers in each flowerhead. Corollas 0.6-1 in (1.5-2.5 cm) long, purple. Flowers at margins of flowerheads not enlarged as in some species of Centaurea. Achenes about 1/8 in (2.5-3.5 mm) long, white or brown streaked, smooth, with no pappus. The species epithet calcitrapa is derived from the word caltrop, a weapon with protruding spikes used in ancient times to obstruct the movement of cavalry. (Description from Hickman 1993, Roche and Roche 1990, Tutin et al. 1976)

|

|

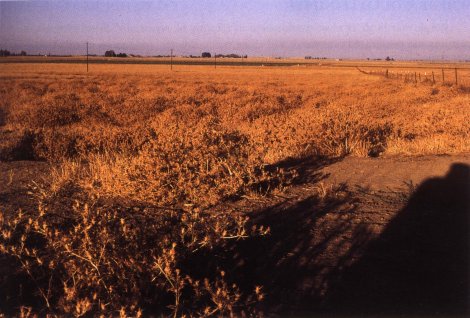

WHERE WOULD I FIND IT?

|

Purple starthistle is

most troublesome in recently or repeatedly disturbed areas such as pastures and

overgrazed rangelands and along roads, ditches,

and fences, usually below 3,000 feet (1000 m) elevation. It is most prolific on

fertile soils and seems to prefer heavier bottomland and clay soils (Roche and

Roche 1990). Found along the coast from San

Diego to

Humboldt

County, in the northern

and southern Coast

Ranges, and across the

Central

Valley to the Cascade

and Sierra foothills, it is particularly abundant in the San Francisco Bay Area

and north into Marin, Solano, Napa, and

Sonoma counties (Amme

1985, Havlik 1985).

åÊ

|

|

WHERE DID IT COME FROM AND HOW IS IT SPREAD?

|

Purple

starthistle is native to the Mediterranean region of southern

Europe

and northern Africa

(Roche and Roche 1990). It was first detected in

California

near Vacaville

in 1886 (Robbins 1940) and has recently become established as a rangeland and

pasture pest as far north as Washington.

Purple starthistle reproduces only by seed. Since the seeds have no pappus, it

is likely that they have been dispersed long distances in hay and straw and on

farm and ranch machinery. Some seeds may also be dispersed moderate distances as

are those of tumbleweeds, remaining in the flowerheads until after the plants

have died, broken off at the soil, and rolled before strong winds.

åÊ

|

|

WHAT PROBLEMS DOES IT CAUSE?

|

Purple starthistle is a pest of pastures, and in the San Francisco Bay

Area it is regarded as a major problem (Roche and Roche 1990). It has also

invaded some grassland preserves, notably within the East Bay Regional Park

District and at the Jepson Prairie Preserve northwest of Rio Vista. It is not

clear whether purple starthistle can form dense infestations in grasslands not

subject to heavy grazing or other disturbances, but it is suspected that it can

and that it will replace desirable native species.

åÊ

Purple starthistleÛªs stiff, sharp spines and bitter taste discourage

feeding by cattle, deer, and rodents (Amme 1985). It replaces palatable species

in some grazed areas, and dense stands of mature plants can make areas

inaccessible to livestock and humans (Roche and Roche 1990). Its spines are

thicker and stronger than those of yellow starthistle and do not fall from the

plants in autumn as do those of yellow starthistle. Because of this, forage that

may grow in infested areas during fall and winter after purple starthistle has

senesced may be inaccessible to grazers.

åÊ

åÊ

|

|

HOW DOES IT GROW AND REPRODUCE?

|

|

Purple starthistle reproduces only by seed.

It is a rosette-forming herb.

Most plants remain in the rosette stage for one year, bolt, flower, and set seed in the second growing season, and then die.

Some individuals may complete their life cycles in one year in extremely favorable circumstances (annual) or only after several years in unfavorable circumstances (monocarpic perennial) (Roche and Roche 1990).

The seeds have no pappus, and most are deposited below or near the parent plant.

Viable seeds can be found in the heads of senesced plants, which may break and be blown long distances, scattering seeds as they go (Amme 1985).

Longevity of seed in the soil is unknown.

|

(click on photos to view larger image)

|

|

|

HOW CAN I GET RID OF IT?

|

|

|

Physical control:

|

Manual

methods: Grubbing or digging can control small infestations. Amme (1985)

reported that purple starthistle populations were sharply reduced after three

years of hand grubbing efforts at the Las Trampas site in the

East

Bay

Regional

Park

system. Plants should be cut at least two inches below the soil surface early in

the growing season. They are easiest to see after they have begun to bolt, but

they should be cut before they begin to flower in order to prevent the release

of viable seed. If plants are cut after they have begun to flower, they should

be removed from the site and destroyed. Follow-up treatments will be necessary

as field tests indicated that 10-15 percent of plants cut below the root crown

resprouted (Roche and Roche 1990).

åÊ

Mechanical methods: Mowing is not an effective method of control. The

rosettes are too low to be cut and plants that have already bolted often respond

to mowing by producing multiple rosettes. Mowing plants that have begun to

flower will spread the cut flowerheads, which may still be capable of dropping

mature seed.

åÊ

åÊ

|

|

Biological control:

|

Insects and fungi: There is no biological control program for purple

starthistle. Two species of Bangasternus seed head weevils that have been

introduced to control yellow starthistle (Centurea. solstitialis) are

reported to have Û÷biotypesÛª that feed on purple starthistle in Europe but there

are no plans to introduce these to North America.

åÊ

Grazing: Conventional grazing by sheep or cattle will not control purple

starthistle and in fact can promote it, because grazing animals usually avoid

this plant and selectively feed on species that would otherwise compete with it.

It has been suggested, however, that rotational grazing practices with short

graze periods followed by recovery periods may reduce purple starthistle and

promote grasses and other species that compete with it (DiTomaso

pers.comm.).

åÊ

åÊ

|

|

Chemical control:

|

Clopyralid, 2,4-D and dicamba provided effective control of purple

starthistle but had little or no effect on grasses (Whitson et al. 1987).

Late winter or spring application is recommended because the seedlings and

rosettes are most sensitive at this time (Roche and Roche 1981). Amme (1985)

reported that a 1 percent solution of glyphosate killed all purple starthistle

along a rocky road shoulder.

åÊ

åÊ

|